Water transfers and interconnections

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

The UK has a high degree of spatial variation in its water resources. The most densely populated areas and much of the key farmland is located in the more water scarce areas of the south and east, whereas the water abundant areas are in the north and west. Therefore, like many other countries, strategies and systems are required for moving our water around. Much of this is achieved via water transfers and interconnection systems.

A national water grid is often heralded as a solution in the UK, but the reality is not that simple. Transfers and interconnections can operate over a range of distances and do not necessarily involve large scale infrastructure.

This article aims to define the various types of transfer and interconnection and highlight how they can contribute to achieving water security.

[edit] Background

The need to move water has always presented a logistical challenge for civilisation. Since ancient times, the development of engineered solutions to transport water has allowed towns and cities to grow and farmland to propagate great distances from the nearest plentiful water source. The Romans were renowned for their grand aqueducts, though earlier peoples in Greece, Asia and Egypt built and operated innovative supply systems also.

In the UK, large scale water transfer systems were in place as early as the 17th Century, such as the New River, which moved water from Hertfordshire to London. Later, the Victorians constructed an extensive water transfer network to cope with the demands of an increasingly urbanised population, and much of this infrastructure remains in use today.

As the world’s population continues to grow and weather patterns become more affected by climate change, the organisations tasked with securing a resilient and effective supply of water face bigger challenges than ever.

In the UK, the winter of 2013-14 was the wettest on record, but between 2010 and 2012 we experienced two of our driest. Water companies have had to think more strategically and to incorporate innovative solutions into their resource management plans – water transfers and interconnections may have an important part to play.

Large infrastructure solutions to the UK’s water security have often been suggested in the media, such as the idea for a national water grid or a canal transporting water from the plentiful north to the dry south and east. This has led to considerable debate regarding the merits and challenges of such solutions. During these discussions it has become clear that there are different understandings of the terms ‘water transfer’ and ‘interconnection’. Broadly, a water transfer is the physical movement of water from one location to another, on any scale and by any means, to satisfy some human need.

An interconnection refers to the joining up of two existing water sources or supply systems which facilitates a water transfer between the two. The water resource areas may be adjacent to each other and involve only a short transfer or straightforward re-direction of water, or they may be separated by a greater distance with water transferred via a more extensive infrastructure system.

The interconnection can be within one water company or provider’s resource area or can involve movement of water between separate water companies or providers. Series of interconnections, via displacement chains of supply-demand rebalances, may also be employed to transfer water over longer distances, rather than by using long pipelines.

The type of water involved (i.e. treated or untreated), the distance it is moved and a number of other related factors can all vary significantly. The major classifications of transfer and interconnection are defined below.

[edit] Bulk raw water transfer

A bulk raw water transfer is the transmission of untreated water (or minimally treated water, i.e. not directly fit for human consumption) using canals, pipes, rivers, aqueducts or other means, from one region to another. The water may originate from a surface water source, a spring or groundwater, or potentially could be treated wastewater effluent.

The transfer may be entirely within a region covered by a single water company/provider or between regions covered by separate water providers. An example is the 40-mile long aqueduct system that supplies the San Francisco, California area from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

In many cases, bulk raw water transfers are moving water that is relatively clean to begin with, thereby alleviating concerns about the potential for long-term fouling of the transmission system itself, e.g. the Great Manmade River in Libya transports freshwater from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System over vast desert distances with minimal treatment.

In the case of bulk raw water transfers that are done via existing rivers or non-covered canals, there may be ecological concerns associated with the proliferation of invasive aquatic species (e.g. zebra mussels), or the spreading of chemical/microbiological contaminants from one water environment to another.

[edit] Bulk treated water transfer

Bulk treated water transfer is the transmission of water that has already been treated to drinking water quality standards from one region to another, typically through buried pipes but also potentially through covered aqueducts or by other means (e.g. tanker trucks or bottled water during emergencies). The transfer may be entirely within a region covered by a single water company/provider, or between regions covered by separate water companies/providers.

This type of transfer may occur between water companies that operate in adjacent regions, if there are existing connections between the water distribution networks of the regions. There may be concerns associated with maintaining drinking water quality with this approach, e.g. if a newly introduced or blended water matrix into a distribution network influences the taste, odour, colour, corrosivity, disinfectant concentration, or other parameters at the consumer’s tap.

[edit] Intra-company transfer

An intra-company transfer is the movement of water from one location to another, entirely within one water company’s boundary.

All water companies have a number of separate sources of water within their boundary area, often of several different types. Each source will provide a different deployable output and will react to weather patterns in a different way. The challenge for water companies is how best to use and distribute water from all its sources to ensure effective supply to customers throughout the year.

Weather and rainfall patterns go a long way to determining when a particular source of water can best be utilised. A groundwater source relies largely on winter recharge as summer rainfall, usually minimal, is just absorbed by soil moisture deficit or runs off into the river with no recharge to the aquifer. A direct river abstraction has a minimum deployable output based on the lowest river flow, generally in late summer, and is most restricted by low summer rainfall.

In contrast, winter rainfall will usually result in higher flows which can simply flow past the intake. Small reservoirs are one season critical and will refill each winter, even in low rainfall conditions. Larger reservoirs may well not refill during a dry winter and are 18-month critical drawdown. Re-use schemes and desalination plants are not affected by weather conditions and could run all the time, however most have high energy requirements and can produce high carbon emissions.

Therefore no one drought, summer or winter, would affect all of a water company’s sources in the same way. By interconnecting their sources, a water company can overdraw sources that are not in a critical condition at any one time, e.g. using river abstractions in winter and spring and saving reservoir storage and groundwater for use in summer. This system is called conjunctive use and the interconnections are achieved via pipelines.

There are cost considerations as well as environmental. For instance, upland reservoirs generally supply by gravity and have low operational costs whilst lowland and reuse sources have considerable pumping and/or treatment costs. Thus, when weather conditions allow, and sources are connected, a water company can use the cheaper sources rather than the more expensive sources.

Most water companies now have many of their sources interconnected across all the water resource zones within their boundaries to ensure that all customers have the same standard of service.

The barriers to this practice can be where the waters meet drinking water standards but are of different types with different tastes, such as a hard water and a soft water. Extensive interconnection infrastructure can also be expensive to build and maintain such as some systems that operate in rural areas, e.g. East Anglia.

[edit] Inter-company transfer

An inter-company transfer refers to the movement of water from one water company to another, i.e. across one or more company boundary.

Where a water company has a shortfall in one or more of its water resource zones, which cannot be covered by interconnections from within its boundary area, it may import water from another company or provider. Water companies in the south-east of England – where drought and population pressures are more pronounced – are commonly the recipients of water via such schemes.

Water companies are actively encouraged to develop interconnections with neighbouring water companies in order to increase overall resilience to drought and reduce the risk of environmental damage due to over-abstraction of their own water resource areas. We are now seeing more and more interconnection schemes, both proposed and actual, appearing in water companies’ water resource management plans.

Many inter-company transfers are currently in operation in the UK and some have been in place since Victorian times. They may be in operation all or most of the time, only when they are needed, or unused (newly proposed interconnections for times of extreme drought).

An example of such a scheme is the Ely Ouse to Essex Transfer Scheme which is operated by the Environment Agency. During normal conditions, Essex’s water company – Essex & Suffolk Water – can face a shortfall of around 7% of its own water resources in supplying its customers. Water that would otherwise flow into the sea is taken from the Ely Ouse at Denver, Norfolk – within the boundary of Anglian Water – and channelled via the scheme’s infrastructure down to Essex. In dry conditions, this transfer can supply up to 35% of Essex’s requirements.

[edit] Water trade

Water trading is a transfer method related to inter-company transfers and refers to the systems and framework by which water can be bought and sold between different water companies.

Trading is an important way of making the best use of resources on a national scale and increasing overall resilience to drought. It can also offer companies a cost-effective alternative solution to securing their water resources, in comparison with, for example, desalination, which is expensive and energy-intensive.

In the UK, Defra’s 2011 white paper Water for Life set out the intentions for increasing water trades via offering incentives to water companies. Government and regulators in the UK continue to consider how to remove unnecessary barriers and encourage increased trading. Reforms included in the Water Bill, which received Royal Assent on 14 May 2014, are aimed at delivering a revised market model for trading and allowing water companies greater choice in obtaining alternative water resources.

[edit] River regulation from upper reservoir to lower abstraction

Reservoirs provide storage sites for water, the release of which is regulated according to the need for water of downstream customers.

Most good reservoir sites are in the upper reaches of rivers where the sides of the valley are steep and create a natural basin for holding water when a dam is installed downstream. The towns and cities that are supplied by the reservoir are commonly situated around the lower reaches of the river, historically because it provides a good source of water.

Water could be conveyed from the reservoir to the town by pipeline, but this would denude the river of some of its flow, particularly important during low flow conditions. Therefore it is often the case that transfer involves raw water being released from the reservoir (via the dam), passing down the river, and then being abstracted closer to where it is needed.

Many of the more recently constructed reservoirs in UK work on this principle. An example is Wimbleball reservoir on Exmoor which releases water into the Exe for abstraction to provide the water supply to Exeter.

Barriers to such systems can be where there are sources of pollution discharging into the river, which are difficult to treat.

[edit] Long-distance transfer

In some locations, typically highly populated towns and cities or economic centres situated in water scarce regions, an effective solution can be to transfer water from a plentiful source over a long distance (i.e. hundreds of kilometres), via man-made structures such as canals, viaducts or pipelines.

The fundamental problem to be solved by this type of transfer is a scarcity of water at the region in need. However, in order to justify the costs of construction, the scale of the infrastructure required, the energy demands of transferring the water (e.g. via pumping) plus other environmental or economic impacts – such projects must normally be the only viable water supply solution to an extreme water scarcity situation and/or yield a number of additional benefits.

An example of such a scheme is the Lesotho Highlands Water Project – Africa’s largest water transfer scheme, built at a cost of billions. Water is transferred from Lesotho’s water-abundant mountain region to Gauteng province in South Africa, via a series of dams, transfer pipelines and pumping stations.

As well as supplying water to South Africa’s population and mining industry, the scheme has provided significant income to Lesotho’s economy, brought about improvements to transport infrastructure around the scheme sites and the creation of a significant source of hydropower at the dam locations – almost enough for Lesotho’s entire national energy need.

Other examples of long distance transfer schemes are the Colorado River to San Diego scheme in America, China’s South-North transfer project and the Great Man-Made River Project in Africa, which supplies northern Libya with water from the aquifers of the Sahara.

This article was originally published as 'What are water transfers and interconnections?' by ICE on 12 November 2015. It was written by Ben McAlinden.

--The Institution of Civil Engineers

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Aqueduct.

- Desalination.

- Dove Stone Hydropower.

- Drainage.

- Dual purpose reservoirs.

- Groundwater control in urban areas.

- How canals work.

- Incumbent water company v undertaker.

- Mains water.

- Manhole.

- Marine energy and hydropower.

- Public water supply.

- Rainwater harvesting.

- Reservoir construction.

- River engineering.

- Sewerage.

- Sewerage company.

- Sustainable urban drainage systems.

- Sustainable water.

- Swales.

- Types of water.

- Water conservation.

- Water consumption.

- Water cycle.

- Water engineering.

- Water Industry Act 1991.

- Water management.

- Waterway.

Featured articles and news

Farnborough College Unveils its Half-house for Sustainable Construction Training.

Spring Statement 2025 with reactions from industry

Confirming previously announced funding, and welfare changes amid adjusted growth forecast.

Scottish Government responds to Grenfell report

As fund for unsafe cladding assessments is launched.

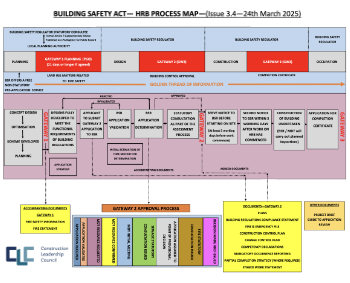

CLC and BSR process map for HRB approvals

One of the initial outputs of their weekly BSR meetings.

Architects Academy at an insulation manufacturing facility

Programme of technical engagement for aspiring designers.

Building Safety Levy technical consultation response

Details of the planned levy now due in 2026.

Great British Energy install solar on school and NHS sites

200 schools and 200 NHS sites to get solar systems, as first project of the newly formed government initiative.

600 million for 60,000 more skilled construction workers

Announced by Treasury ahead of the Spring Statement.

The restoration of the novelist’s birthplace in Eastwood.

Life Critical Fire Safety External Wall System LCFS EWS

Breaking down what is meant by this now often used term.

PAC report on the Remediation of Dangerous Cladding

Recommendations on workforce, transparency, support, insurance, funding, fraud and mismanagement.

New towns, expanded settlements and housing delivery

Modular inquiry asks if new towns and expanded settlements are an effective means of delivering housing.

Building Engineering Business Survey Q1 2025

Survey shows growth remains flat as skill shortages and volatile pricing persist.

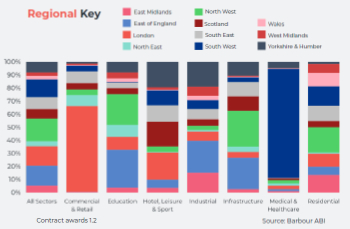

Construction contract awards remain buoyant

Infrastructure up but residential struggles.

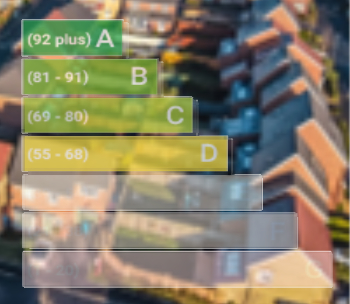

Warm Homes Plan and existing energy bill support policies

Breaking down what existing policies are and what they do.

A dynamic brand built for impact stitched into BSRIA’s building fabric.